Although wild camping has long been legal in Scotland, 92% of England’s countryside remains off-limits. Now Dartmoor National Park is at the centre of a battle to reclaim the outdoors.

I

In the shadow of Belstone Tor – a distinctive hill topped by granite rock formations – standing stones formed a circle in the cropped grass. Some say the stones were once maidens, petrified into rocks for dancing on the sabbath; others warn that to move the stones is to welcome a curse. In reality, the “Nine Maidens” mark a Bronze Age burial chamber, one of the countless ancient sites hidden across Dartmoor National Park’s 368sq miles of moorland, valleys and forests.

I hiked a faded path etched into the ground over millennia, picking my way through piles of granite boulders to the summit of Belstone Tor, 479m above sea level. In a country where there’s no right to roam across 92% of the countryside, the open moorland I saw stretching south – devoid of field boundaries and fences – has long provided a natural escape for outdoor enthusiasts.

For decades, Dartmoor National Park – located in the south-western county of Devon – was the only place in England where “backpack camping” (wild camping without needing to ask the permission of the landowner) was legal, but a controversial High Court decision made in January 2023 threatened to outlaw this tradition. This sparked a nationwide debate on public access in the English countryside, with hikers, mountain bikers, nature lovers, climbers and horse riders rallying on the moors to protest. In July, the momentous decision was overturned and backpack camping once again became legal in the national park.

The “Nine Maidens” stone circle marks the site of a Bronze Age burial chamber (Credit: Richard Collett)

“Southern England has very few big spaces and fewer where one could actually get lost. People are drawn to that, and the combination of tors, ponies, steep valleys and miles of undulating moorland is instantly recognisable,” said Inga Page, as she explained the attraction of Dartmoor National Park. “There’s also the dark side – the bogs, the fog, the prison – which makes it so much more than just a pretty landscape.”

Southern England has very few big spaces and fewer where one could actually get lost

A lifelong walker and environmental activist, Page quit her job in 2012 to spend the last decade leading walks on Dartmoor after founding the tour company Dartmoor Walks This Way. Like many people before her, Page was captivated by the stark natural and human history of the moors.

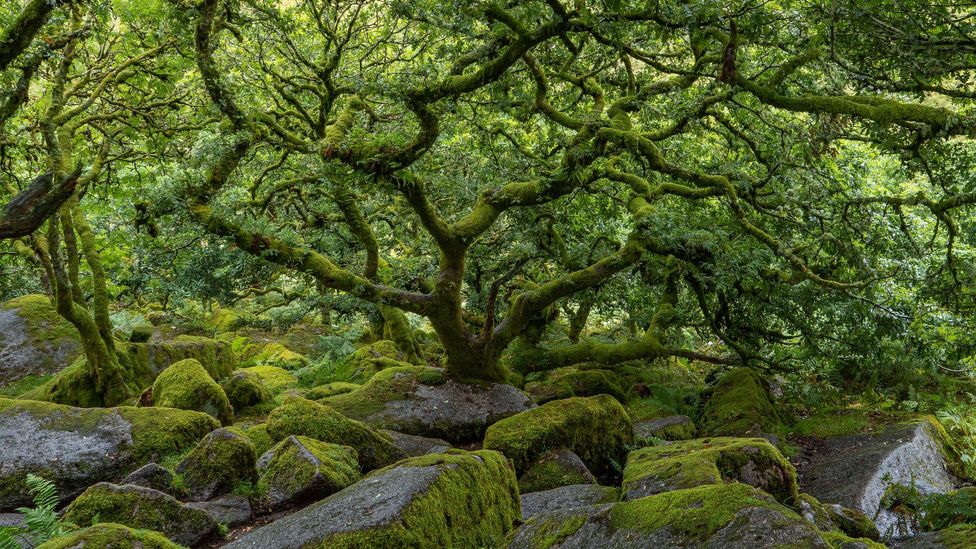

The great granite tors (65% of Dartmoor is granite), which look like they were stacked by giants, began forming some 280 million years ago, while the oldest cairns, menhirs, stone circles and burial sites were raised by Dartmoor’s earliest human inhabitants as early as 3500 BCE. Legends, superstitions and folk stories – like those of the beast-like “Wisht Hounds” that stalk the moors, or the “Hairy Hands” that steer unsuspecting drivers to their deaths – abound on Dartmoor, while the seemingly bleak landscape is, in fact, filled with rare species of flora and fauna, including surprising pockets of temperate rainforests that hikers might chance upon.

Although Dartmoor is known for its rocky tors and windswept moors, it’s also home to pockets of temperate rainforest (Credit: Chris White/Getty Images)

Designated as a national park in 1951, Dartmoor is the remnant of a medieval “commons” system once found all over England that gave commoners (landless people of non-noble standing) certain rights of access over “common land”, which was public land where they could graze livestock or collect wood for fires and cooking. From the 16th Century onwards, much of this common land – and the rights of access that went with it – was closed off, as private landowners began enclosing it for private agriculture.

Unusually for England, up to 37% of Dartmoor National Park (and 75% of the park’s upland moors) is still considered to be common land, although all of that land is still privately owned. Kelly Rich, the communications lead for the Dartmoor Preservation Association, an organisation that has been protecting Dartmoor since 1883, explained how these historical common rights led to the national park’s liberal recreational rights, including the freedom to roam when hiking, horse riding, biking and rock climbing.

“The 1985 Dartmoor Commons Act was a framework that enshrined both commoners’ rights and recreational rights,” she said. “And recreational rights were hard fought at the time to be included.”

It was always assumed that backpack camping – which allowed for individuals and small groups to spend one or two nights on remote moorland within designated areas of the park, so long as all their gear was carried in a backpack – was one of these recreational rights, and certain areas of Dartmoor had traditionally been designated as backpack camping zones.

The High Court of England’s contentious ruling gave Dartmoor landowners the right to move wild campers on (Credit: Richard Collett)

In 2011, wealthy hedge fund manager Alexander Darwall purchased 4,000 acres of land, named the Blachford Estate, within Dartmoor National Park. Twelve years later, he challenged the legality of backpack camping in the High Court of England, leading to the contentious ruling in January 2023 that gave Dartmoor landowners the right to move wild campers on.

Kate Ashbrook, general secretary of the Open Spaces Society, explained that backpack camping had never been explicitly listed in the 1985 Dartmoor Commons Act, simply because it had always been assumed that it was an integral part of recreational activities on Dartmoor anyway.

Hammocks: A higher form of camping

The Open Spaces Society, as well as the Dartmoor Preservation Association, Dartmoor National Parks Authority and many more organisations, immediately challenged the verdict, though, and found legions of supporters across England.

“It got everyone going,” said Ashbrook, “People were realising that access could be taken away, and that one landowner could have this devastating impact.”

On 21 January 2023, 3,000 people marched across Darwall’s estate in one of the biggest land-access protests England has ever seen. Among the protestors’ placards was a large puppet depicting the likeness of “Old Crockern”, a mythical guardian spirit of Dartmoor who is said to summon fearsome Wisht Hounds when the land is under threat. The protestors channelled the spirit of protests past, too, including the famous Kinder Scout Trespass of 1932 that saw some 500 ramblers protesting a lack of access to the Peak District and paved the way for legislation that created England’s first long-distance walking trails and national parks.

In protest of the ruling, people gathered to summon the ancient defender of Dartmoor, “Old Crockern” (Credit: Jonny Pickup/Getty Images)

Covid-19 had shown the nation how important it was to have easy access to the outdoors, and given that the Open Spaces Society, England’s oldest conservation society, has been protesting for increased access to the countryside since 1865, the ruling on Dartmoor went against the general trend in Northern Europe that’s seen more areas of the outdoors opened up to the public. In Scotland, wild camping has been legal since 2003, while in Sweden, for example, there’s long been a public Freedom to Roam and camp.

“I believe in more access to nature for all people, and I believe in educating people to do this responsibly,” said Henriette Lofstrom, who leads multi-day hiking and camping trips on Dartmoor. She explained why the loss of backpack camping was so keenly felt on Dartmoor. “It does something to us as modern humans, when we leave our cities and busy modern lives behind for a stint to sleep close to the stars. Sure, we can go for a day walk and end up in the pub afterwards, but to carry on walking for a string of days and sleep out is entirely different. It’s the full banquet, not merely the starter.”

Okehampton is located on the northern flank of Dartmoor National Park (Credit: Richard Collett)

I’d made the journey to Belstone Tor via the town of Okehampton on the Dartmoor Line, which closed in 1972 but was relaunched in December 2021. After a 30-minute train ride from Exeter and an hour’s walk from the station, I was standing atop Belstone Tor feeling the force of the Dartmoor wind.

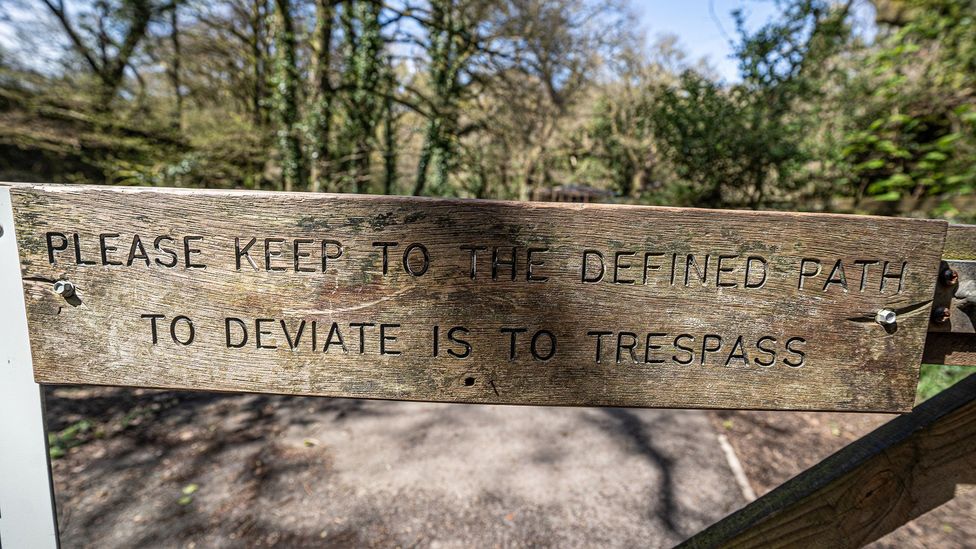

From the summit of the tor, I followed old tracks across the moor to a valley near Okehampton that was lined with mossy oak trees. After leaving the boundaries of Dartmoor National Park, I found myself in front of a gate that was labelled with a warning: “Please keep to the defined footpath. To deviate is to Trespass”.

Despite the High Court concluding that wild camping is indeed a recreational right on Dartmoor, it remains the only place in England where wild camping is allowed without permission. Because of this, many campaigners see the decision as just the start, and are looking to emulate Scotland’s democratic access rights. As Ashbrook said in a press release following the successful appeal: “Following this judgment, Dartmoor remains one of only a handful of places in England where there is a right to backpack camping without the landowner’s permission. We should like to see that right extended, and we shall campaign with other organisations to achieve this.”